The first decade of poor harvests ended with a good crop in 1775. This first high yield crop was made possible by adequate rainfall for the first time after many years of drought. In addition, the colonists began to plough more acreage when they replaced their crude Russian sokhi with iron-tipped ploughs. The colonists also became adept at breeding draft horses to pull the tilling equipment. Commercial fertilizers were unknown and the farmers practiced a three and four year crop rotation. Several vast fields were maintained around each colony to insure adequate supplies of each agricultural commodity.

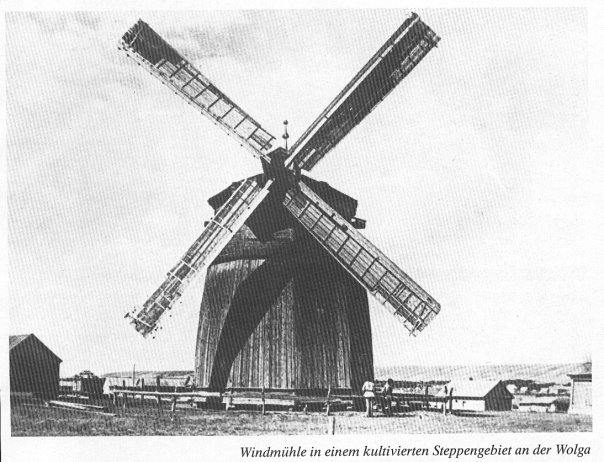

Farm work began in the spring as the snows melted revealed a growth of winter rye in at least one of the large colony fields. Volga Germans were heavy consumers of rye flour, and it was planted in late August following summer rains. Sunflowers, spring grains and potatoes were planted in late March and April. Sunflowers were processed for oil in various mills in the region. Millet was the third most important grain crop in the colonies and was also sown in the spring. Millet was used to make Hirsche, a coarse porrdige. Oats, barley, both used mostly as animal fodder, were also spring crops.

Hemp and flax were also grown for domestic clothing needs.

Cabbage, melons and pumpkins were gathered from communal garden near the villages. Sauerkraut was a staple food for the Volga Germans that was prepared in the fall. Garden vegetables planted in the Hinnerhof (yard adjacent to each home) included carrots, onions, sugar beets, tomatoes and cucumbers. Apple, pear and cherry trees were planted in both family gardens and large communal orchards. Most fruits were preserved through sun-drying. Wild pear trees and strawberries were common. Other berry varieties were also available. Mushrooms were harvested in August. Licorice root harvested in the fall was used to make Steppetee - a favorite Volga German drink.

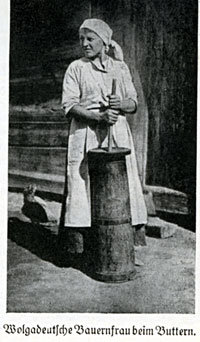

Large cellars were constructed and filled with irregular blocks of ice insulated with straw to keep dairy products and fresh meat safely stored in the hot summer months. The ice was collected early in the year along the banks of the Volga and in the mill ponds during the spring thaw.

Families gathered for an annual butchering bee in November or early December. Fruit tree cuttings were used to smoke sausage and other meat products made by the colonists.

With the long harvest season over, fall plantings completed, and produce sold or stored, the villagers gathered to celebrate their bounty in an exuberant festival, the Kerb. This event signaled the end of the field season as the people prepared for the long Russian winter. Isolated on the steppe, the Volga German villages became quiet and self-sufficient until the next spring.

When Volga Germans became rich enough to want to leave their villages and set up as independent farmers, instead of operating as communal village farmers, they bought themselves land, but usually named the farms after their own surname - e.g. Diesendorf, Schmidt, Seiffert, Chutor or Khutor. A Chutor was a small settlement or outpost beyond the boundaries of the colony. They might very well have taken extended family along with them, or field labour employees, or other poorer families to work the land, so it would become 'farmstead'.

By 1940, the Saratov region had in fact become Russia's bread basket. The primary agricultural crop was wheat. Also grown was rye, barley, oats, and millet. The grains were sold in the city of Saratov.

In the United States, the Volga German immigrants were instrumental in the development and growth of the sugar beet industry.

Koch, Fred. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977.